The final memories

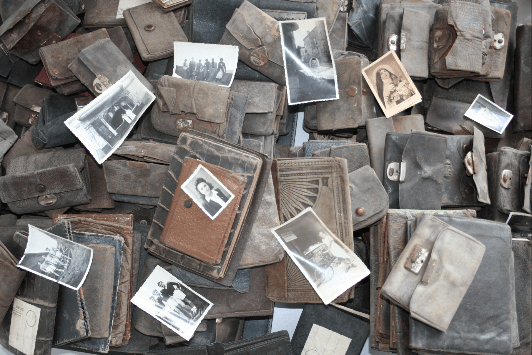

Wallets with photos, engraved wedding rings, costume jewellery, letters and documents: when they arrived at the concentration camps, prisoners only carried what they happened to have on them when arrested, or what they were able to hide on their person before being deported. Arolsen Archives still protects these personal effects belonging to around 2,500 former prisoners.

“Effects” is an old word originally meaning luggage. It later came to mean the personal items that prisoners had to surrender when they went to prison, with the expectation of being reunited with them on their release. Like prisons, concentration camps also had “effects chambers”. In many camps, the Nazis kept the prisoners’ belongings, labelled with their owners’ names, but often only to keep up an appearance of lawfulness and order – until the prisoners were murdered. If the prisoners were transferred to other camps, the SS would send their effects after them. But it was different in the extermination camps, where perpetrators simply collected the victims’ property and transported it away. The Nazis turned this stolen property into money and used it for their own purposes, including to fund their war machine.

These effects are everyday objects that grant a glimpse into life before captivity

while emphasising just how great their loss was: personal items such as wallets,

identity papers, photos, letters and certificates, as well as individual pieces of

costume jewellery, cigarette cases, wedding rings, pocket- and wrist-watches

and fountain pens that belonged to the former concentration camp prisoners.

How did the objects come into the Arolsen Archives?

The effects mainly come from the concentration camps Neuengamme and Dachau; there are also smaller items, for example from the Gestapo in Hamburg. In 1963, the Arolsen Archives received a total of around 4,700 effects with the task of returning them to their owners. Most of the items had been obtained shortly after Neuengamme concentration camp had been liberated by the British army. The soldiers found the property of the prisoners at Neuengamme concentration camp in Lunden, Schleswig-Holstein. It was what remained of the prisoners’ property office at Neuengamme that had been brought there. The British authorities impounded these personal belongings. In 1948, they handed the property over to the Central Claims Registry with the task of returning it to its owners.

The effects, which were brought to the Arolsen Archives in 1963, included

purses and wallets, initially unsorted, which could mostly be attributed to

specific prisoners. These often included mementos of friends and family,

such as photos.

The management and return of the effects from Dachau concentration camp were organised by the prisoners themselves after the liberation of the camp. In 1963, the remaining envelopes were eventually transferred to the archives in Bad Arolsen via various German agencies and institutions.

Fates from all over Europe

The collection of effects reflects the dehumanisation that took place under the Nazi reign of terror in Europe and provides tangible evidence of the camp system and the varied life stories of the victims. In many cases the effects belonged to forced labourers who had often been accused of the most trivial of supposed offenses, such as having contact with Germans, and then imprisoned and set to work, mostly in the arms industry. Arrested resistance fighters from all over Europe were also deported to concentration camps. In their reprisals, the Nazis also detained civilians who had had no involvement and labelled them as “political prisoners”.

Wanted: Neonella’s relatives

Neonella Doboitschina from Russia, born on 11 October 1923, was one of the many women forced by the Nazi regime to work in order to keep its war economy running. On 5 May 1944, the Gestapo deported the young student to the women’s concentration camp in Ravensbrück. She was transported to Neuengamme concentration camp on 31 August 1944. Her subsequent fate is unknown. Her effects include some pieces of jewellery as well as many photos with inscriptions – memories of happy times. Her friends called her Nelly.

A rarity: effects of Jewish people

There are only a few effects of Jewish concentration camp prisoners in the Arolsen Archives. The items mostly belonged to Jews from Hungary who had been deported as forced labourers to Germany in the last months of the war. This was very much the exception, since most deportations from Hungary went to Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp, where prisoners were immediately murdered.

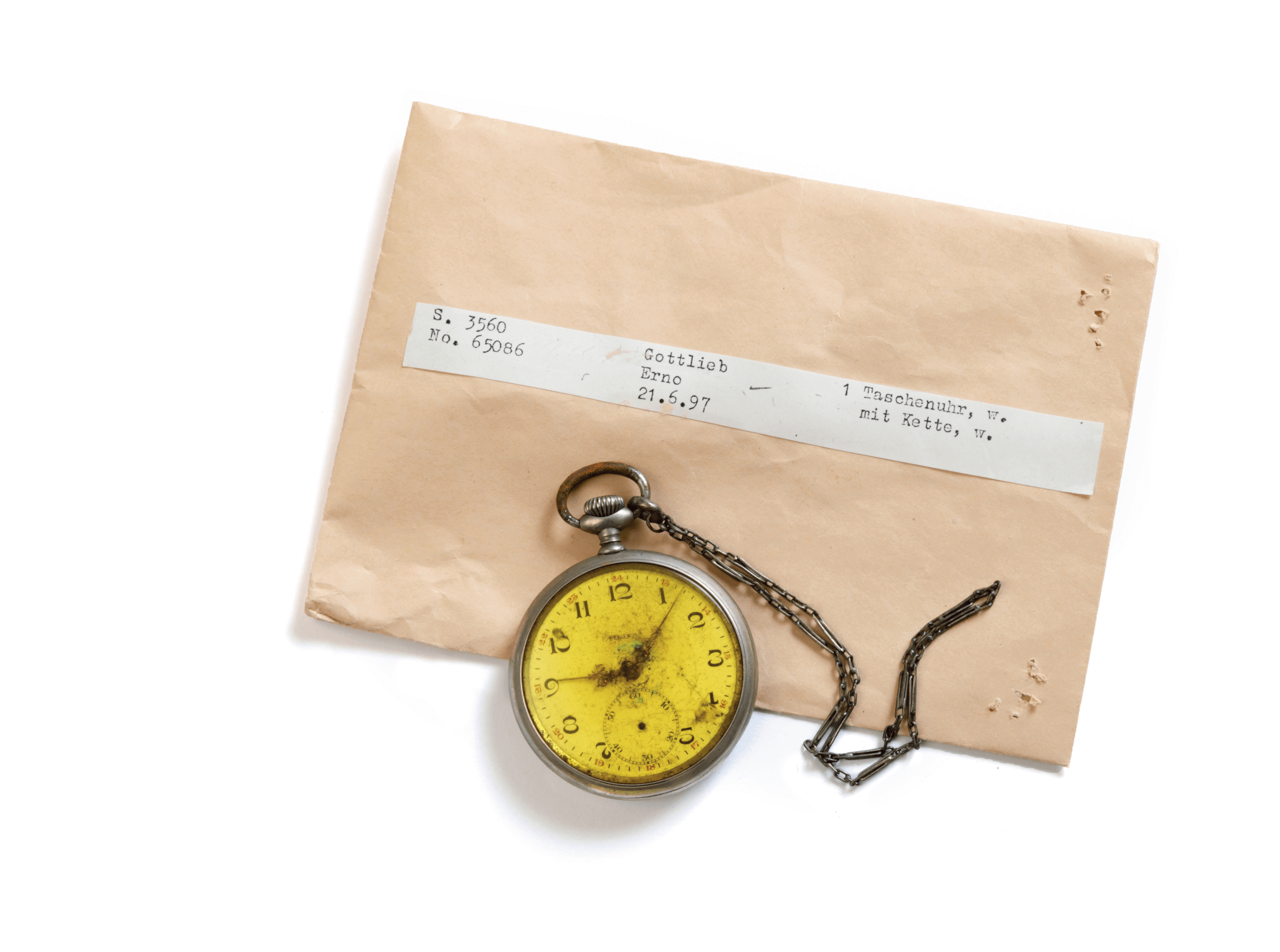

Ernö Gottlieb was one of 880 Hungarian Jews transported from Budapest to Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg in November 1944. The Nazis deported the Jewish accountant to the Wilhelmshaven subcamp – a naval dockyard where he had to carry out extremely heavy labour. He died on 25 March 1945 as a result of the brutal conditions. He is buried in Wilhelmshaven. This is his pocket-watch, which the Arolsen Archives would like to hand back to his relatives:

Prisoners brought to the Neuengamme or Bergen-Belsen concentration camps on death marches had often lost everything they owned. There are also hardly any effects from Sinti and Roma prisoners.

Stigmatised for life

One important group of prisoners represented in the archives are those labelled “asocial” and “professional criminals” by the Nazis. For the relatives of these prisoners, this stigmatisation is often painful and fraught with shame. To this day the victims have not had their names cleared, nor have they received any compensation. An investigation into these fates is therefore long overdue, including for the relatives of those labelled as “homosexuals”.

Almost all owners are known

The effects in the Arolsen Archives are highly unusual, as such collections do not exist in the memorials at the sites of former concentration camps. While the collection is very small and originates from only a few sources, on close inspection, the items show connections to almost every concentration camp. In combination with the original documents from the camps in our comprehensive archive, they offer insights into their owners’ tragic histories. The owners of most objects in the Arolsen Archives are known.

The institution’s staff began researching the owners of the effects and their relatives as early as 1963. They worked with lists of names that had been drawn up by various agencies and compared these against the archive’s Central Name Index, which contains details of around 17.5 million people. At the same time, enquiries were also made into whether the names were on the lists.

« I still find it fascinating. After 80 years on, I’m holding something in my hands that belonged to my grandfather and was surely very important to him. »

Christel Gottschalkvisited the Arolsen Archives in person to collect a pocket-watch and some pension certificates that belonged to her grandfather Max Wernicke.

Research and digitisation make returning effects easier

Over the years, photos of all the effects have been published in the online archive of the Arolsen Archives to make them more visible and easier to return, as well as to further document the items after they are returned. A research project also ran from 2009 to 2011, in which just under 900 effects were examined and re-recorded. For many objects whose owners had previously remained unknown, this made it possible to attribute names. Right from the start, the aim of all research was to return the personal objects to their persecuted former owners or their relatives.

Active search

It is often difficult to find out whether the victims have any living relatives and, if they do, the countries they live in. That is why the Arolsen Archives initially published a list of names on their website in 2011, followed by photos of the effects in 2015. Since late 2016, the institution has run the #StolenMemory campaign, in which it actively searches for relatives in order to be able to return more personal items than previously possible. In many countries, the Arolsen Archives also work with volunteers and institutions such as the Red Cross in order to find relatives.

Some families donate the effects to regional museums and memorials, where they can be displayed to show the fates of individual victims. At the request of her relatives, this broach belonging to French resistance fighter Irène Rossel was given to the Museum of the Résistance in Joigny, France, in 2018.