Former concentration camp sub-camp now a meeting place for neo-Nazis: Kamenzer Straße in Leipzig

With over 5,000 prisoners, the HASAG Leipzig sub-camp was Buchenwald’s largest women’s sub-camp. The camp’s main building has been privately owned since 2007 -– and since then, it has repeatedly attracted attention on account of right-wing rock concerts and right-wing martial arts meetings that have been held there. The Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial has now issued a public statement calling on the city administration to take action.

The men and women who were imprisoned in the „HASAG Leipzig“ sub-camp (a men’s camp was also set up in the fall of 1944) had to perform forced labor and manufacture weapons and ammunition for Saxony’s largest armaments company “HASAG” (Hugo Schneider AG).

Office for the Protection of the Constitution: property is “used by right-wing extremists”

The main building of the women’s sub-camp was located at Kamenzer Straße 12 in North East Leipzig. Dormitories were set up in the high-ceilinged halls, while the first floor housed the infirmary, the registry office, and the camp canteen. The area for washing and the chambers that served as detention cells were located in the basement. The building is the only surviving relic of a concentration camp sub-camp within the boundaries of the city of Leipzig – and for nearly 15 years, it has been owned by a man who is thought to belong to the neo-Nazi scene. In recent years, Kamenzer Straße 12 has mostly been the subject of headlines along these lines: “A former concentration camp in Nazi hands: a new boxing club sets up shop in Kamenzer Straße” or “Leipzig police prevent far-right music festival.” chronik.LE, a project that documents fascist events “in and around Leipzig,” has repeatedly carried reports about memorial plaques having been destroyed. In April 2021, a swastika flag was allegedly found during a raid on the premises of the “Sin City Boxgym” boxing club. Saxony’s Office for the Protection of the Constitution lists the site as a “property used by right-wing extremists.”

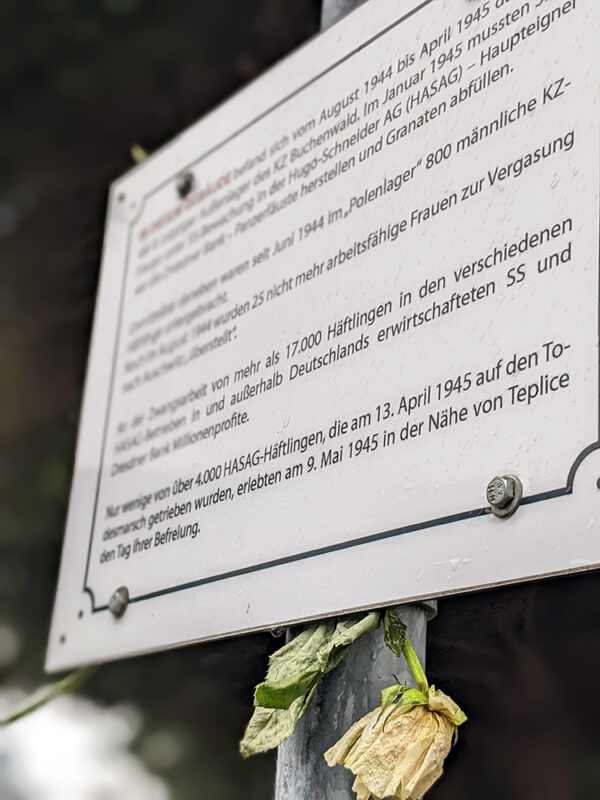

This small plaque is currently the only reminder of the fact that the inconspicuous building in Kamenzer Straße used to be a concentration camp sub-camp.

Josephine Ulbricht has been working for the Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial since 2008. She has never once seen the owner of the building, and he has never made any public comment on the debate. It is unclear whether or not he knew about the building’s history when he bought it: “We don’t know anything about that,” she says.

Leipzig City Council: Plans for an information board to go up by 2025

In 2020, Leipzig City Council acknowledged the historical significance of the site and passed a resolution that includes plans to install an information board by 2025 at the latest. This could be too late for many of the contemporary witnesses who are still alive today. Estare Kurz (now Estera Weiser) is one of them. She was born on April 13, 1945, the day the sub-camp was liquidated. In 1951, she was able to emigrate to the USA with her mother Anna and father Abraham, who was in Theresienstadt when liberation came.

Anna and Estare Kurz after their liberation from the concentration camp HASAG in Leipzig in the summer of 1945 (Photo: Estare Weiser)

Anne Friebel, who also works at the Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial, came across Estare Weiser’s story while doing some research in the Arolsen Archives in the summer of 2019. Initial attempts to contact her as a contemporary witness came to nothing, but in the spring of 2020, she happened to contact the memorial site herself. She is 76 years old and now lives in New York City.

“We knew that a department of Leipzig City Council was thinking about inviting Estare Weiser over for a visit. We feel strongly that the memorial plaque should be inaugurated before her visit, so we put that point to them.” Talks have since been held between the Memorial and the Cultural Office of the city of Leipzig. “We are confident that the memorial/information plaque will be inaugurated this summer. Unfortunately, it is unclear whether Estare Weiser will be coming to Leipzig soon,” Ulbricht said.

»I think the city could do more to explore its Nazi past. Things are not the same as they were ten years ago, when it could give you a bad image; it’s very accepted now. Munich is planning to build a place of remembrance in Neuaubing, and in Berlin, remembrance has its own place too. I don’t know why things are different here.«

Josephine Ulbricht, Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial

When the proposal to grant the building the status of a historic monument was rejected in late 2020 because too many changes had been made to the building’s substance since 1945, one thing was very clear to Josephine Ulbricht and her team: “We have to do something.” In the fall of 2021, they decided to submit a statement to the Mayor of Leipzig, Burkhard Jung, calling for things to change. “I think the city could do more to explore its Nazi past. Things are not the same as they were ten years ago, when it could give you a bad image; it’s very accepted now. Munich is planning to build a place of remembrance in Neuaubing, and in Berlin, remembrance has its own place too. I don’t know why things are different here.”

Public Statement on Holocaust Remembrance Day 2022

The Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial published their statement on January 27, 2022, the 77th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Floriane Azoulay, the Director of the Arolsen Archives, employees at various memorials, professors, and politicians were among the first to add their signatures. It is now possible to sign the statement online too as a public pledge of support.

The statement includes the following concrete demands:

“The building and grounds at Kamenzer Straße 12 must…

- become publicly owned. (…)

- be maintained and preserved in accordance with its status as an archaeological and historical monument. (…)

- be accessible to the Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial and other stakeholders involved in remembrance policy so that they can visit it in the future with survivors and their relatives and use it for educational and remembrance work.

- be honoured by the City of Leipzig as a key historical place of remembrance with regard to the concentration camp system and Nazi forced labour.

“The days that followed the publication of our statement were quite exciting,” remarked Josephine Ulbricht in early February. “We were pleased with the response from the general public and from the press. Now, we have to think about the next steps: What do we do with the signatures? How do we want to proceed?”

The windows of Sin City Boxgym. A swastika flag was reportedly found here in April 2021. The club maintains that the flag was actually found in some nearby rehearsal rooms.

However, the city’s initial response to the demands was quite disappointing: Because the property is privately owned and is not protected as a monument of special historic interest, “serious sales negotiations have, unfortunately, not yet begun.”

If Josephine Ulbricht could make a wish for the coming year, it would be this: “I hope the information board in Kamenzer Straße will be inaugurated. If the city were to buy the building, that would be very good, of course. But even if someone else buys it – and seeing as it’s private property, that could happen – we’d like the city to get involved and help ensure that it becomes a place of remembrance.”

The aim of our #LocalRemembrance initiative is to give local remembrance efforts a voice to promote the valuable and important work they do. Because the systematic persecution of millions of people did not take place in a few central locations. The story of Kamenzer Straße in Leipzig, like many other similar stories, shows that sites of persecution, terror, and exploitation could still be on your doorstep – without the general public having any knowledge of their existence.