Displaced

Persons in Arolsen after

1945

Who were these former forced laborers and concentration camp inmates who came to live in Arolsen and worked for the Allies? How did they organize their everyday lives after years of persecution and war? A new volume in the “Findings“ series uses selected documents to throw light on the history of the Displaced Persons who worked for the predecessor institutions of the Arolsen Archives and helped trace missing persons and document fates.

Not only did millions of documents on the victims and survivors of Nazi persecution find their way to Arolsen after 1945, people who had experienced persecution came too. At times, there were over 1000 people living as Displaced Persons (DPs) in the region during the postwar period. Most of them had experienced imprisonment in concentration camps and forced labor. Many millions of DPs were living away from their home countries throughout Europe at the time and needed help in order to be able to return to an independent life. In 1946, there were more than 450 DP camps in the US American occupation zone alone. The camp in Arolsen was set up especially to accommodate personnel for the tracing service.

The new publication „Zweierlei Suche – Fundstücke zu Displaced Persons in Arolsen nach 1945“ (title of the English edition: “Two Kinds of Searches – Findings on Displaced Persons in Arolsen after 1945”) consists of 80 pages packed with information on the history of these Displaced Persons, which is still largely unknown. One of the key aspects it covers is the DPs’ work for the Central Tracing Bureau (CTB), which was set up in 1945 before being succeeded in 1948 by the International Tracing Service (ITS), known today as the Arolsen Archives. The foreign language skills of the DPs were particularly useful.

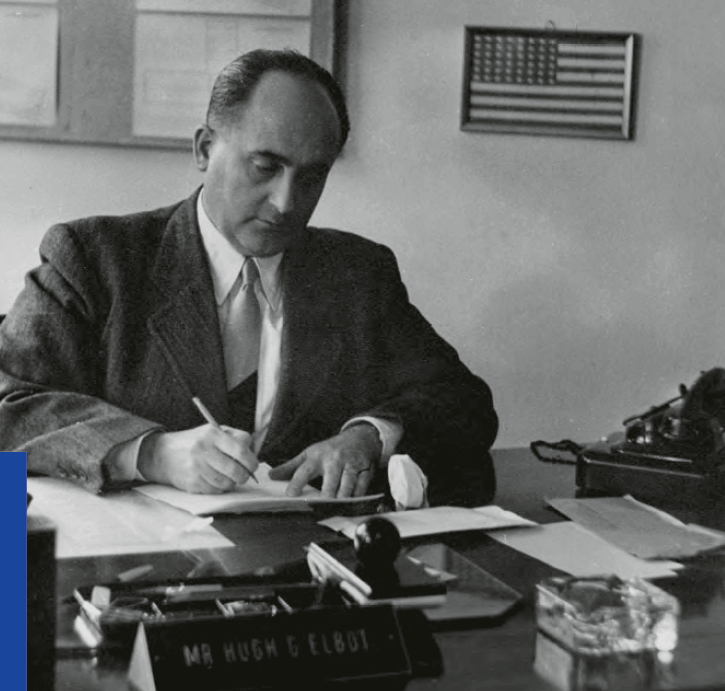

»[The] work encompasses the sorting of cards with Slavic names in the alphabetical-phonetic card files, the interpretation and translation of documents from the East and a precise knowledge of the clerical tasks that were carried out in the forced labor and concentration camps. In addition, there is the translation of inquiries in Slavic languages.«

Hugh G. Elbot, Chairman of the ITS Administration in May 1952

In addition to a selection of documents from the archive, three essays deal with the subject: Christian Höschler, Deputy Head of Research and Education at the Arolsen Archives, provides an overview of the history of DPs in postwar Europe and the current state of research. Isabel Panek, Research Assistant, describes where the DPs came from, how they were accommodated, how they were looked after, their day-to-day lives, and the courses their lives went on to take. Finally, Silke von der Emde, Associate Professor of German Studies at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, highlights the contribution DPs made to setting up the archive, tracing missing persons and providing information in response to inquiries. This volume complements the contents of the permanent exhibition, “A Paper Monument”, which was opened in 2019.

The volume also presents individual biographies such as that of Eduard Muszynski, for example, who was persecuted as a “political Pole”. Up until the spring of 1945, he had been imprisoned in the Arthur sub-camp of the Buchenwald concentration camp, which was located in the barracks in Arolsen from 1943 to 1945. When the sub-camp was evacuated shortly before the end of the war, he managed to escape while being transported to the Flossenbürg concentration camp. He returned to Arolsen after the war because he did not have anywhere else to go. It was there that he married Rosemarie Voigt, who had been persecuted as a “half-Jew”. Three years later, the couple emigrated to Australia along with their young daughter. Before he emigrated, Eduard Muszynski had worked for the ITS.

This volume is a new addition to the well known “Findings” series and appears in the new corporate design of the Arolsen Archives. The book is available in German as of 29 October 2019 and costs €9.90. Orders can be e-mailed to id@arolsen-archives.org. German and English versions are now available online on the website of the Arolsen Archives. All new publications from the Arolsen Archives will be provided for download free of charge.