#StolenMemory third anniversary: global search

Arolsen Archives launched “#StolenMemory” three years ago: since then, we have been actively searching for the families of former concentration camp prisoners whose personal belongings are stored in our archives. Initially, many of our employees doubted that they could trace such relatives. Now, more than 350 families have been reunited with memorabilia such as jewellery and photos – and in three cases, even the survivors themselves got them back. We look back at a search operation that also changed staff perspectives.

“StolenMemory has extended our mandate,” explains Anna Meier-Osinski, Head of the Tracing Department. “For decades, Arolsen Archives had simply responded to inquiries: Holocaust victims or their relatives contacted us in search of information. But with this initiative, we took a proactive approach.” This raised lots of questions among staff. How will someone react when they receive their deceased father’s wristwatch after 70 years? How do we approach people who may be completely unaware of their relative’s fate? Will families want to know anything at all about these belongings?

Despite all the misgivings, it is clear that most families are delighted to receive news from Arolsen Archives. There have only been two instances when people didn’t want to take the items. Often, entire families come to Bad Arolsen to collect their deceased relative’s belongings – as in December 2018, for example, when the extended family of the resistance fighter Braulia Canovas Mulero travelled from France and Spain. They had only heard that Braulia’s jewellery was stored in Bad Arolsen via a #StolenMemory campaign on Spanish radio.

Intensive global search

#StolenMemory is an initiative that involves experienced staff from the Arolsen Archives Tracing Department searching for the owners of objects, or their families, in order to return these. It also supports a poster exhibition that has so far been displayed in France, Poland, Luxemburg, Greece and Germany. Many more locations are planned for 2020, for example in Russia.

These exhibitions feature the belongings of former concentration camp prisoners from the respective country or region, in the form of missing posters. Often, journalists and appeals in the local media also help to increase awareness of the search. In many countries, historians or other volunteers assist the Arolsen Archives. Without their commitment and regional knowledge, it would often be impossible to conduct intensive local research and visit families in person.

Detective work in Belgium

Georges Sougné, here with a suitcase of objects in the permanent exhibition of the Arolsen Archives, helps to find families in Belgium and France. He often visits the relatives of the victims personally and is always impressed by these encounters. During his family research, Georges receives important information and useful tips on where to look next. Often, he stays for several hours and has conversations that can be very intimate and moving.

Bringing the fate of victims to life

Arolsen Archives accepted the belongings with the aim of reuniting them with their owners. However, the items not only have a personal, emotional value for the families and victims themselves. They can also help document Nazi persecution. Some of the families therefore hand the belongings over to concentration camp memorials, where they can be used for education and enlightenment. Arolsen Archives also implements #StolenMemory as an educational project, with pupils in Poland, for example, who are currently researching the fate of victims from their region.

The personal belongings of concentration camp prisoners provide direct testimony as to the extent and systematic nature of Nazi crimes. They are an essential part of our major exhibition on German history.

Fritz Backhaus, Curator of Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin

Important exhibits

Fritz Backhaus is currently endeavouring to acquire the “Haney Collection” for the museum. Wolfgang Haney, who passed away in 2017, had accumulated one of the largest private collections on the history of anti-Semitism and the National Socialist persecution of Jews. It contains around 10,000 to 15,000 documents and artefacts, ranging from anti-Semitic postcards to photographs from the concentration camps. “It also includes prisoners’ personal belongings – the like of which has hitherto been virtually lacking from our collection,” says Backhaus. Although these exhibits would be extremely important for the museum, he wants to find out if there are any relatives who need to be notified about these items. So they are immediately handed over to Arolsen Archives, where staff trace the families and return the belongings if necessary.

The search goes on

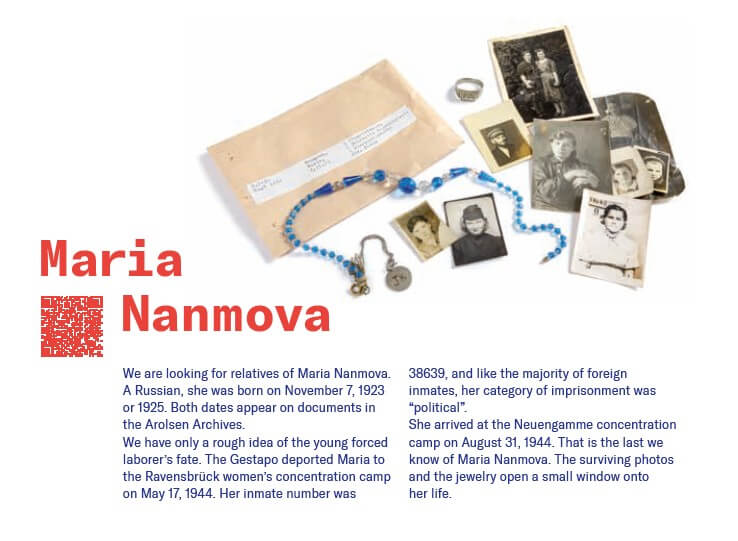

Over the next few years, the investigation team in Bad Arolsen and numerous volunteers will still have plenty to do. Around 2,700 envelopes containing belongings are still stored in the archives. In some cases, the #StolenMemory search for evidence will probably be unsuccessful – but then the items can still perform their important role as a commemoration of and testimony to Nazi persecution.

On very rare occasions, belongings even find their way back to their surviving owners: in October 2019, 95-year-old Lida Labojka was reunited with her jewellery. She had been taken to the Ravensbrück concentration camp by the Gestapo on her 20th birthday.