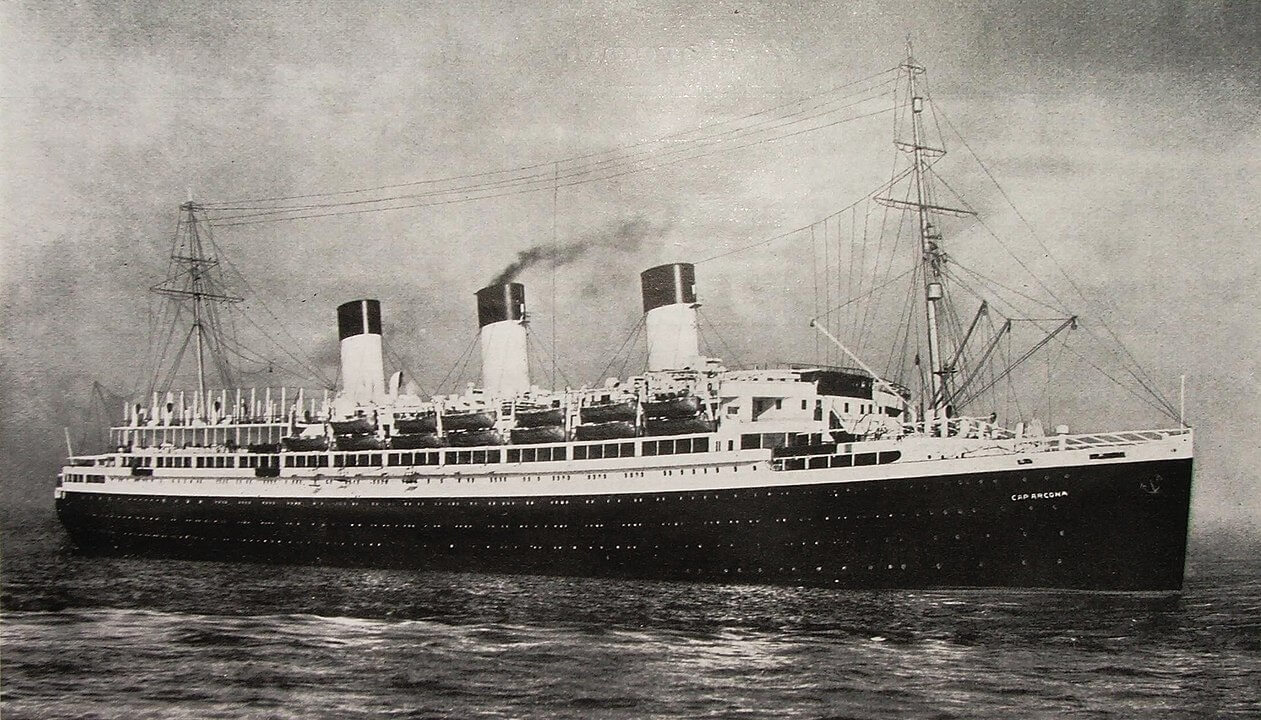

One of the worst maritime disasters ever to occur took place in the Bay of Lübeck in the last days of the Second World War. It caused the deaths of more than 6,000 concentration camp prisoners on May 3, 1945. They were the victims of a terrible mistake: British bombers sank the "Cap Arcona”, a German passenger ship, and the “Thielbek”, a cargo ship, because both ships were thought to be carrying German troops. But the SS had driven thousands of prisoners from the Neuengamme concentration camp onto the ships and was holding them captive on board. Still to this day, a large collection of documents kept in the Arolsen Archives helps give the victims their names back and clarify the fates of family members involved in the tragedy.

Introduction

CLEARING THE CONCENTRATION CAMPS

Prisoners Sent Marching to Their Deaths

No concentration camp prisoner must be allowed to fall into the hands of the Allies - this was the order issued by Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, in April 1945. By then, the British were already approaching Hamburg. To cover up their crimes, the Nazis evacuated the Neuengamme concentration camp – as well as hundreds of other concentration camps throughout the Reich. The leader of the Hamburg branch of the Nazi Party – who was also the Reich Commissioner for Maritime Shipping – consulted with the leader of the SS in Hamburg, and together they took the decision to transfer the prisoners from the Neuengamme concentration camp to two ships anchored in the Bay of Lübeck – the "Cap Arcona" and the “Thielbek."

Floating Prisons

When the evacuation of the concentration camp began, the SS informed the captains of the two ships that they were needed for a "special operation". Both captains firmly refused to let their ships be used as floating prisons, but eventually gave in to the pressure. At the end of April, thousands of prisoners arrived in Lübeck by freight train or on foot and were taken to the ships lying at anchor far out in the bay. The "Cap Arcona", originally a luxury liner built for 850 passengers, suddenly had around 4,300 prisoners on board. Added to that number were about 400 guards and almost 100 crew members. The prisoners had neither food to eat nor water to drink.

They had little chance of survival

British fighter bombers attacked the two ships on May 3, 1945. The "Cap Arcona" was hit by a number of bombs and caught fire. There were no lifeboats for the prisoners; the SS had destroyed all means of escape. Despite being emaciated and weakened by the conditions they had endured in the concentration camps, many people jumped into the cold sea and tried to swim ashore. Guards on the ships and on land opened fire on them as they attempted to flee. The "Cap Arcona" capsized, as did the "Thielbek” which was also hit several times. Of more than 7,000 prisoners on board the two ships, only about 600 survived.

Nowadays, many historians presume that the Nazis provoked the catastrophe and were conscious of the fact that the Royal Air Force might mistake the ships for troop transporters.

Identifying the Dead, Finding Gravesites

The collections of the Arolsen Archives contain extensive documentation on the prisoners from the Neuengamme concentration camp and the disastrous sinking of the two ships in the Bay of Lübeck. Many of the dead were washed ashore in the Bay of Lübeck. They were buried in many different cemeteries in the area - often anonymously and with no information at all about where they originally came from. Skeletal remains of some 3,000 unburied victims still lie on the sea bed where the ships were anchored.

The following tasks remain within the remit of the Arolsen Archives to this day: identifying the dead, searching for burial sites, and reconstructing the paths of persecution of all the victims. This is why the archive also contains comprehensive historical documents about burial sites and about salvage operations continuing on up until the 1950s. The Arolsen Archives also hold quite a large number of personal effects belonging to the prisoners – personal items that were taken away from them on their arrest. We continue to search for the families of the victims to this day so that we can give these mementoes back to them.

Interview

It is still enormously important at an emotional level for the families of the victims to find out what really happened, to obtain certainty about the fate of their missing relatives.

Ramona Bräu,

Documents on the Disaster in the Bay of Lübeck

A conversation with Ramona Bräu, a historian at the Arolsen Archives, about the documents on the sinking of the Cap Arcona.

What documents are there in the archive about the Cap Arcona?

First of all, it is important to understand that a great many documents were produced after the war in connection with the sinking of the Cap Arcona and the Thielbek. The authorities had to deal with the aftermath of this terrible event. Bodies had to be recovered, identified and buried, and bones were still being washed ashore years later. Prisoner numbers on the victims’ clothing were often the only means of establishing their identity. Those who were involved at the time naturally did not have access to the huge quantities of documents from concentration camps that can be found in the Arolsen Archives today. Many of the dead could not be identified.

The online archive now provides direct access to the report filed by the Lübeck water police, reports on the recovery of bodies, the account book of the Thielbek, and photos and a map of the Cap Arcona cemetery of honor in Neustadt Holstein, to mention just a few of the materials available today. There are also a number of documents from the Neuengamme concentration camp that were recovered from the wreck of the Thielbek. And these documents contain clues that helped turn prisoner numbers into names.

The dissolution of the Neuengamme concentration camp and the fate of the Cap Arcona are inextricably linked…

The story of the Cap Arcona is typical of the crimes the Nazis committed in the final phase of the war as they tried to cover up all traces of their terrible deeds in the concentration camps. Prisoners from other concentration camps were transferred to Neuengamme, death marches ended there. The camp was cleared within a very short period of time. The SS transferred several thousand prisoners to the ships in the Bay of Lübeck. Often, victims’ families knew nothing of the fate of their loved ones and searched for them in the wrong places. Not until they submitted an inquiry to the Arolsen Archives were they able to find the right documents. Finding out that a brother, father, or grandfather was among those who died in the Bay of Lübeck comes as a very painful surprise. We can sometimes even tell the families where their loved ones are buried at last, more than 70 years later.

During the hasty evacuation of Neuengamme, the prisoners’ personal effects were also removed from the camp. An SS man took them with him and hid them in his home village. They were found there later by the British Allies. These personal effects are the things that belonged to the concentration camp prisoners and were taken away from them on arrival. These photos, pens, pieces of jewelry etc. were neatly labelled, and when prisoners were transferred to other camps, their personal effects were transferred too. In the 1960s, personal effects from the Neuengamme, Bergen-Belsen, and Dachau concentration camps were added to the holdings of the International Tracing Service, which is now known as the Arolsen Archives. About 2800 personal items are now waiting to be returned to the families of their owners.

How significant are the documents about the Cap Arcona today, 75 years after the events?

It is still enormously important at an emotional level for the families of the victims to find out what really happened, to obtain certainty about the fate of their missing relatives.

Researchers are primarily interested in seeing the whole picture of these historical events. Putting the documents online makes it possible to put them together with reports from survivors and with documents held by memorial sites, associations, and other archives. Documents, personal effects, and biographical data can be brought together in this way and can be found more easily. But even better indexing is required in order for this to work, i.e. the names contained in the documents need to be transcribed so that they can be found. That’s what makes our crowdsourcing project "Every name counts" so important to us.

Personal Effects

The Fates of Polish Prisoners

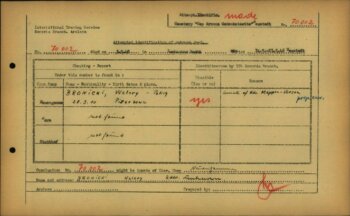

When the German Wehrmacht invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, a period of terror and violence began for the Polish population. Large parts of the country were soon occupied by German troops, who arbitrarily committed crimes against the civilian population. One of the initial objectives of German occupation policy was to annihilate the "leading elements in society." Even before the occupying forces invaded, lists had already been compiled containing tens of thousands of names of members of the Polish intelligentsia. Raids, mass arrests, and mass murders with up to 80,000 victims followed in the first few months already. By the end of the war, it is estimated that the National Socialists had deported around three million Polish people to forced labor camps. The so-called Polish decrees of March 1940 provided official clarification of their inferior status and imposed numerous bans and regulations on them. For example, Polish forced laborers received lower wages than German workers by decree, they were not allowed to leave their place of residence, and contacts with Germans were largely forbidden. From the autumn of 1942 onwards, the SS had the power to send Poles directly to concentration camps for violations or minor offences, but also for "bad" work. Even just being a member of the Polish intelligentsia or the suspicion of belonging to or supporting the Polish resistance was sufficient to justify being incarcerated as a "political prisoner." Concentration Camp Prisoners from Poland Many of the Polish prisoners who died in the 1945 bombing of the Cap Arcona and the Thielbek suffered similar paths of persecution. A central focal point was the Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg. Some Polish prisoners arrived on mass transports from the Auschwitz concentration camp, thousands were deported from their home country by the SS as political prisoners after the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising in 1944, for example, or as forced laborers. Prisoners held in the Neuengamme concentration camp and its sub-camps were forced to do extremely hard work under catastrophic conditions. Of a total of at least 15,000 Polish prisoners, almost 4,000 died of starvation, disease, or as a result of the hard work and the violence they endured. Shortly before the end of the war, the SS sent some of those who survived on death marches to the Bay of Lübeck where they were held on passenger ships. Walery Bronicki Walery Bronicki was one of the prisoners on board. A Polish national, he was born on March 28, 1910, in Pisarzowa. The German occupying forces deported him to the German Reich as a prisoner of war and put him to work as a forced laborer. From January 1945 onwards, he and other prisoners had to build fortifications in Meppen-Versen, a sub-camp of the Neuengamme concentration camp, in order to protect the North German coast from the Allies. Walery Bronicki died in the sinking of the Cap Arcona. In June 1945, during one of the daily salvage operations on the beaches of the Bay of Lübeck, the municipal police in Neustadt registered his prisoner number 70 002 and had him buried near by. Thanks to this registration and the historical documents in their archival holdings, the Arolsen Archives were able to reconstruct Walery Bronicki’s path of persecution in the 1950s and give this hitherto anonymous victim his name back. The Polish man's personal belongings are still waiting to be returned to his family. Kazimierz Biel Seventy-five years after the end of the war, Kazimierz Biel's niece was able to hold her uncle’s birth certificate, which includes a photograph, his student ID card, and other personal documents in her hands. She never met her uncle. Born in Krakow, Kazimierz Biel was just 19 years old when the German occupying forces deported him to the Neuengamme concentration camp. He is one of the many who died on the Cap Arcona. He was buried at the cemetery in Haffkrug in the Bay of Lübeck in October 1950. The Arolsen Archives identified the young Polish man through his prisoner number. Obtaining certain knowledge about his fate has a special significance for Kazimierz Biel’s family: “It brings back the memory of those whose fate during the war was so tragic that it is hard for us to imagine today. For the relatives, these few remaining objects are treasures of inestimable value.”Willi Neurath

The first time the bookbinder Willi Neurath was put in custody was in November 1935 in Cologne, where the Gestapo arrested the twenty-four-year-old on charges of “high treason.” He had been active in the Communist party since his youth, but been expelled from the KPD (Communist Party of Germany) and later joined one of its split-offs. Willi spent his prison term in the jails in Siegburg and Vechta as well as the Esterwegen concentration camp. According to documents in the Arolsen Archives, he was released from that facility on December 24, 1940.

A Strong Marriage

In the prison in Vechta, he had made friends with another inmate from Cologne who asked Willi to visit his wife and bring her a message when he got back home. Willi complied, and during the encounter also met his friend’s stepdaughter, Eva Pakullis. The two fell in love and married the following year. “It was a strong marriage,” Bruno Neurath-Wilson, the couple’s son, recalls. “My mother stood by her husband implicitly and worked with him in the resistance.”

Willi’s second arrest took place on April 23, 1943. Once again, his detention meant an odyssey through various penal institutions. Following several months in investigative custody in Cologne, he was sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp and from there to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. “Once my mother managed to visit him in Buchenwald without making prior arrangements,” Bruno Neurath-Wilson recounts. “She simply addressed a young Lithuanian guard in his—and her—native tongue and told him she wanted to go inside the camp to see her husband. He let her in. A few minutes later, she was standing in the command headquarters demanding to see her husband. And they actually allowed them to meet for half an hour.”

One of the Few Survivors

On October 16, 1944, Willi was sent to the Neuengamme concentration camp. From there, the Nazis transferred him and other inmates to the Cap Arcona, and he was on board when the Royal Air Force bombed it. Since he couldn’t swim, he remained on the capsized, burning vessel. On the evening after the air raid, the British brought him and the few other survivors to land in Neustadt.

What Willi Neurath didn’t know was that his wife Eva was also in Neustadt. She was working as a naval assistant and her detachment had been transferred there to escape the Red Army. Nor did she have the slightest idea that her husband was aboard the Cap Arcona. She had last received mail from him from Buchenwald. In Neustadt, lots of rumors circulated as to who was on board. On the morning after the attack, Eva set out for the beach. “Later she told us over and over about how, in retrospect, she had often asked herself what had drawn her to go down to the beach,” her son remembers. At the entrance to the town, she encountered a grimy, injured man who came straight toward her and started talking to her. It took her a while to realize it was her husband…

Marked by Persecution

The Neuraths remained in Neustadt for a few years; it was there that their two children were born. Willi worked in the municipal administration. He was active in the SPD (Social Democratic Party of Germany) and, with a number of friends, saw to the recovery of the Cap Arcona victims’ corpses and the creation of a commemorative cemetery. For two years he headed the “Political Reparations” department in the interior ministry of the state of Schleswig-Holstein and concerned himself with the fates of many victims of Nazism. That work, but also the consequences of his long, hard years of imprisonment put a burden on him, physically and mentally, a burden from which he never really recovered. “After we moved to Cologne, he was no longer politically active. His strength was depleted—both physically and ‘ideologically,’” his son reckons.

Willi Neurath died in Cologne on April 13, 1961. Bruno Neurath-Wilson has many fond memories of him. He learned a lot about his father’s persecution from his mother—Willi had never talked to his children about it. “In our living room, there was a series of four engravings on the wall,” Bruno tells us. “Motifs of cruelty, suffering, solidarity and help in the concentration camp. For us children, these images were constantly present as we were growing up—maybe they told us something about him without words.”